In this brief article I would like to explore a theory I have been developing for a while: that the extraordinary level of immigration we have experienced in the past several years is a deliberate exercise in what has been called Human Quantitative Easing, that is an attempt to offset inflation from printing money by artificially increasing the stock of people to ‘soak up’ the money. It is possible that others have written on this,1 but I want, in a sense, to ‘get there’ myself, because if multiple people arrive at the same conclusion independently it is usually a good sign of being over target. My analysis will chiefly focus on the UK but I encourage friends in Europe and the USA to apply this to their respective nations.

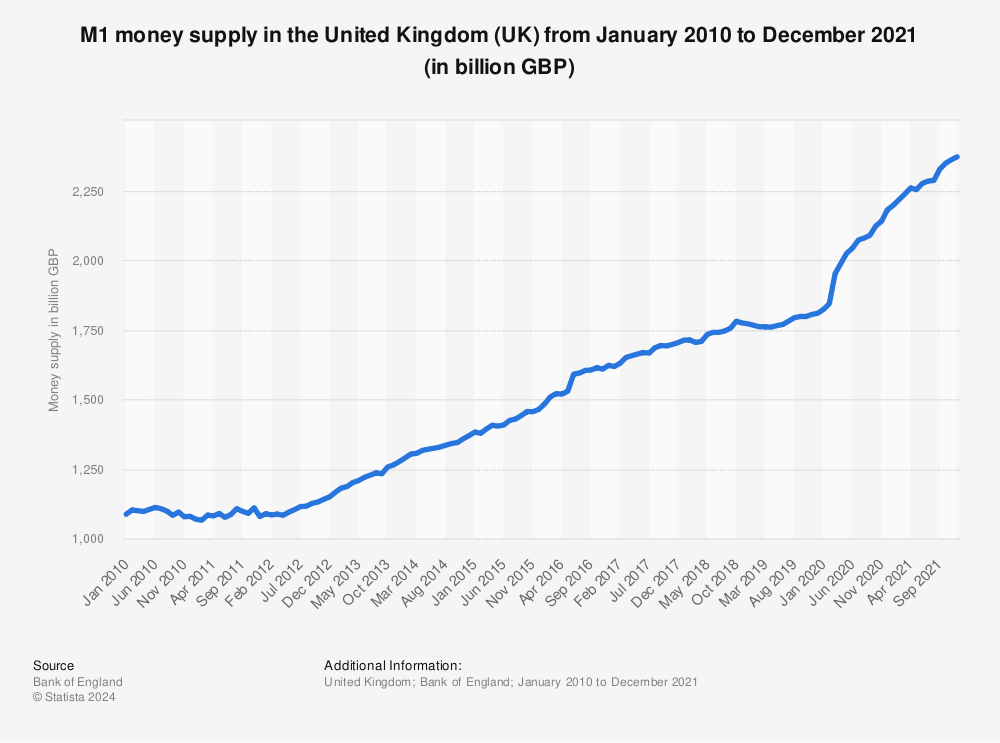

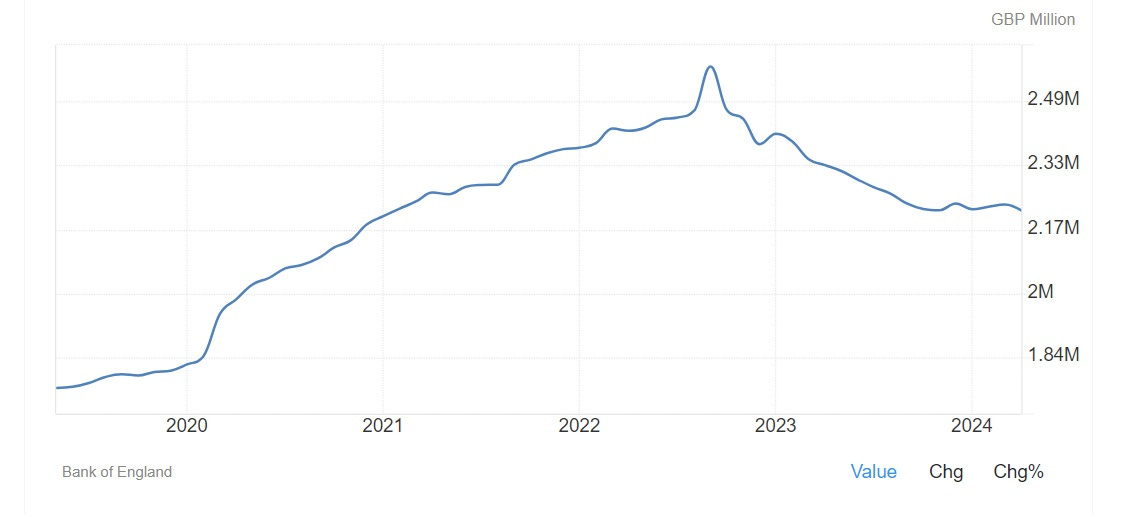

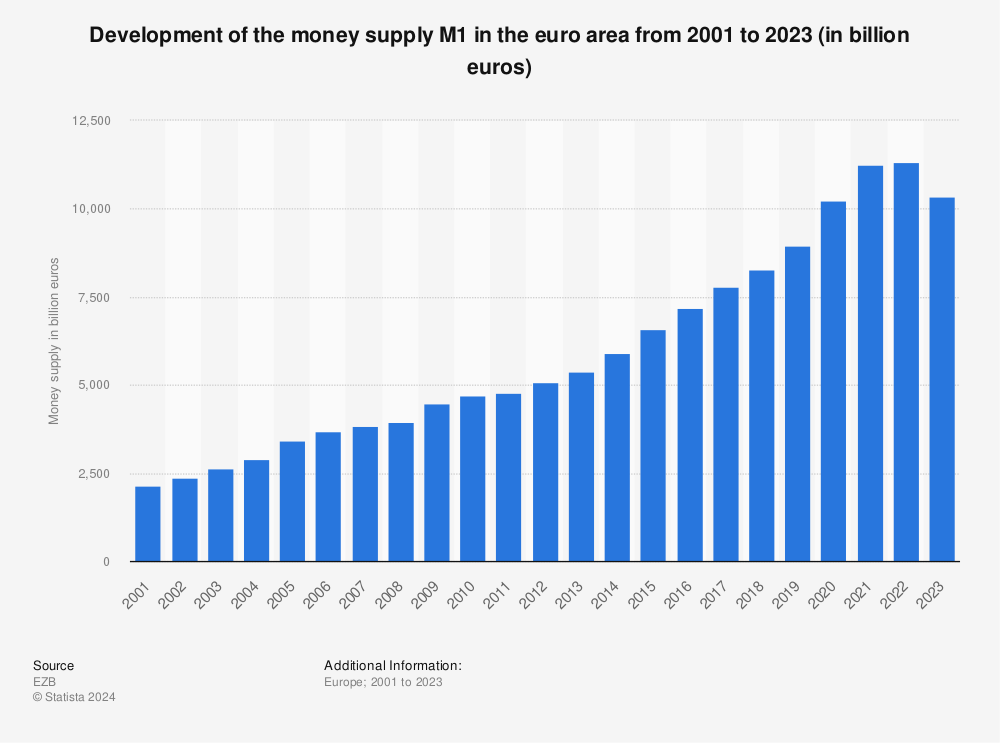

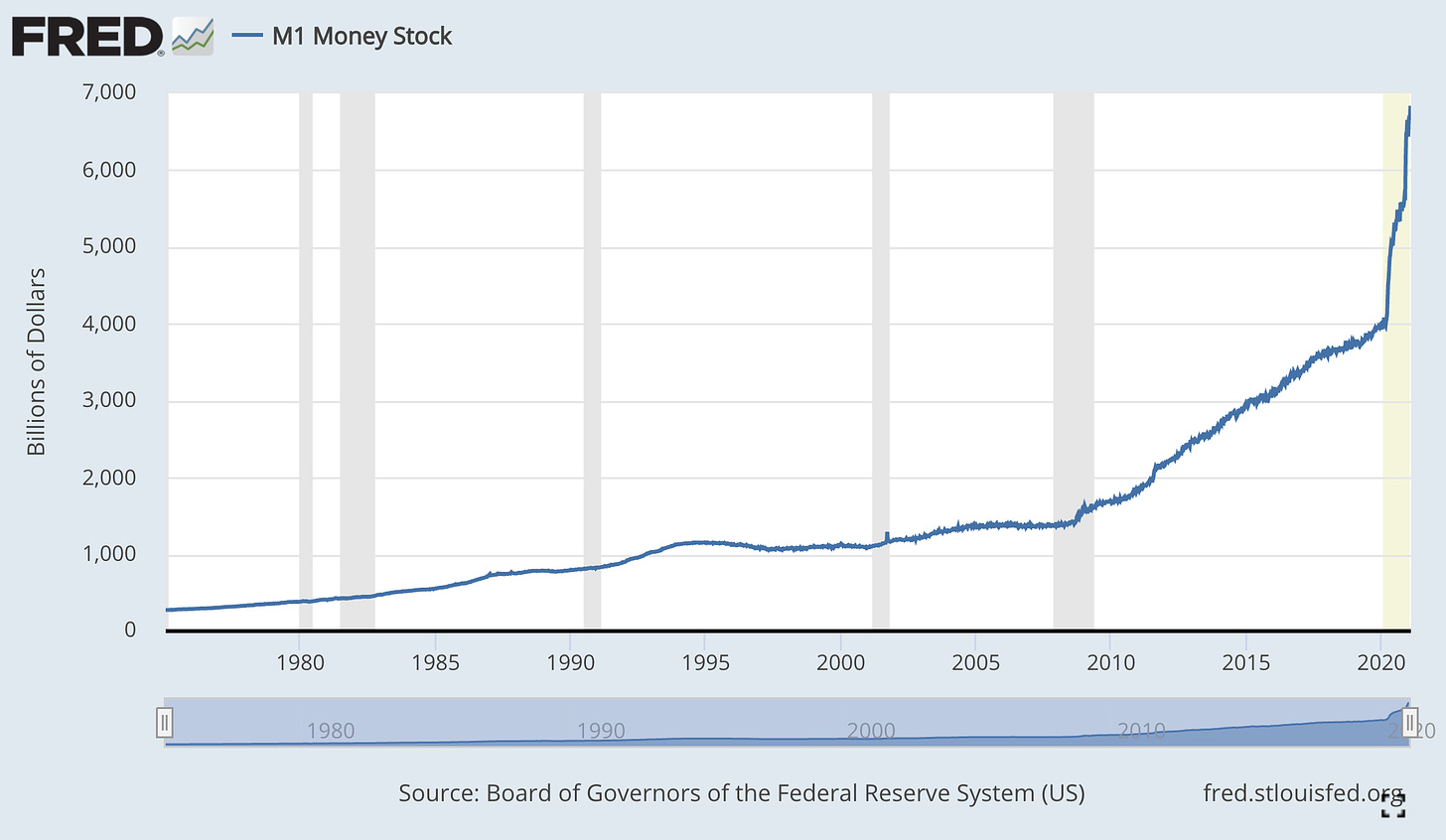

The response to the Covid-19 Pandemic saw a large increase in the money supply. Here are graphs showing M1 Money Supply for the UK, the Eurozone and USA.

The central banks of all three economic areas sought to pay for Covid measures, such as furlough or ‘Trump bucks’ by printing more money. The response to the pandemic at this level was, broadly speaking, harmonious across different nations. Whatever their differences at the level of lockdown policies, governments in general responded to the economic dislocations of Covid in the same way: through government schemes to prop-up wages in the short-term. On top of this, Western economies also got hit with an energy price shock following their – again unified – economic sanctions of Russia following the invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

What made this round of money printing different from previous bouts of QE after the 2008 crisis is that much of that did not occur in the ‘real economy’. To keep this in the layman: ‘M1 Money Supply’ is liquid cash, the money you have in your current account that you can withdraw at a cash point, that you spend on shopping and whatnot. ‘M2 Money Supply’ and beyond is generally ‘stuck’ in some sort of financial institution on their asset balance sheets and is less easily retrieved. If you have some sort of ISA savings account, or a pension fund, you’ll know that this money cannot be immediately cashed out and often there are caveats about how and when it can be cashed out. Previous bouts of money printing, in general, did not ‘make it’ to the M1. That is to say that the majority of it stayed on the asset balance sheets of large investment banks, asset management firms and multinational corporations in illiquid forms. The ‘excess’ money did not hit the ‘real economy’ and thus the rounds of money printing did not cause a great increase in inflation. This was used at one time to mock libertarian economists who had warned of hyperinflation. What was different this time, with the Covid printing, is that the new money did hit the real economy in the form of people’s wages under furlough. It does not take a genius to figure out why this would be inflationary: the exchange ratio between money and all other goods changed. The supply of money increased while the supply of all other goods did not increase. To keep this relatively simple let us use a simple good: an apple.

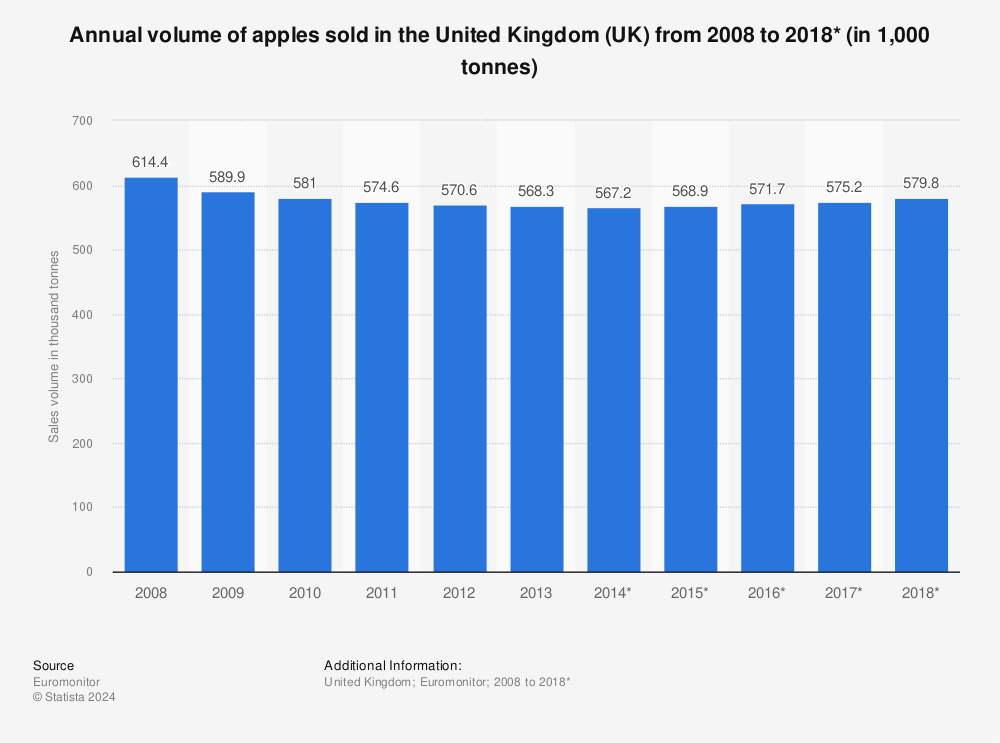

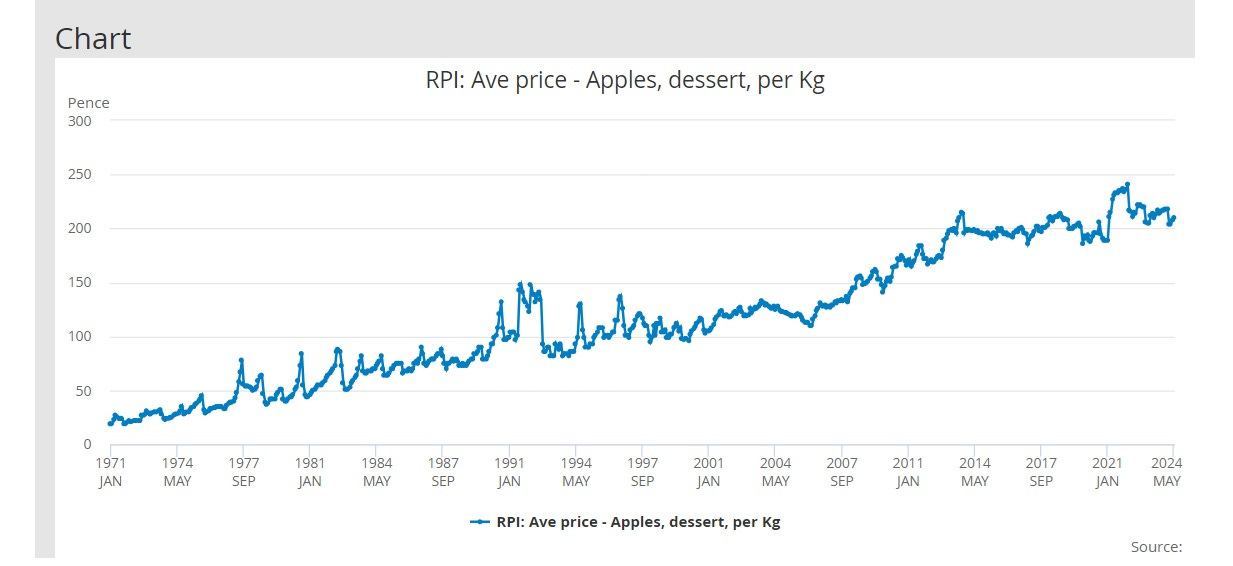

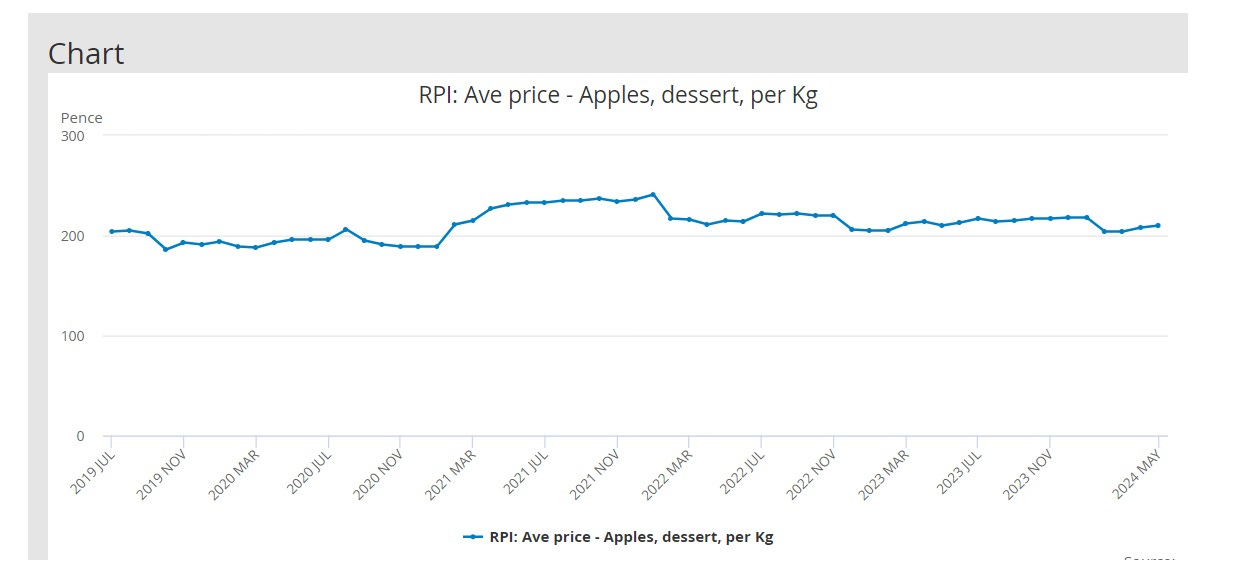

Here you can see total apple sales in the UK are relatively stable: typically somewhere between 570 and 580 thousand tonnes sold a year. We can see roughly speaking that the exchange rate between M1 Money Supply and Apples is about 2.5 billion pounds for every one thousand tonnes of apples. One tonne of apples, assuming an apple is 100 grams, is about 10,000 apples. The exchange ratio between money and one apple is therefore about 250 to 1. Now obviously we do not spend £250 on one apple since this metric alone does not determine the price. Apples have an exchange ratio with all other goods also as well as the subjective valuations of the population of how much they like apples versus all other goods. When all is said and done, people are prepared to spend about 70p on one apple or, according to Tesco, about £2.40 per kilogram. This graph shows that, sure enough, over time the nominal price of apples in the UK have increased.

Industry insiders tell us that in 2023 the total volume of apples fell by 7.5% while average retail prices have risen by 4.4%. We will return to this soon.

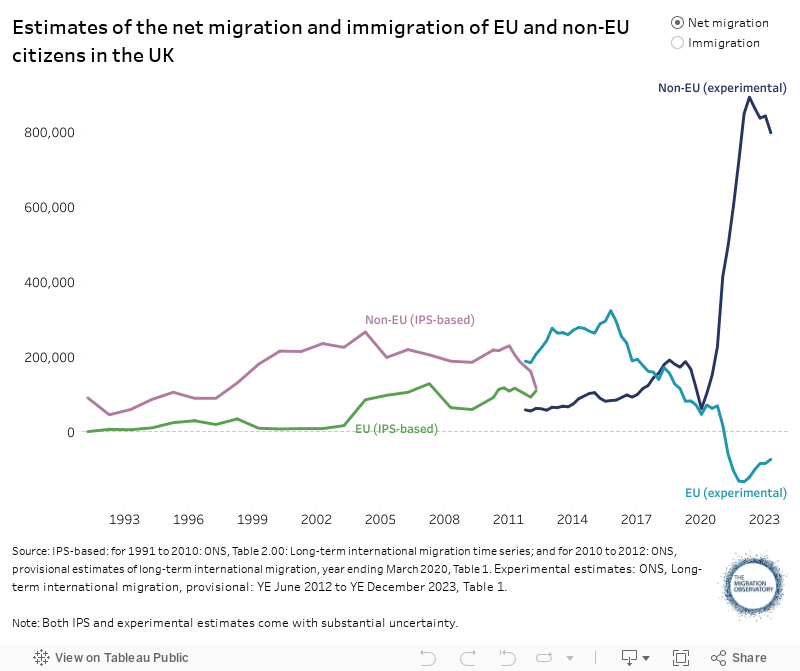

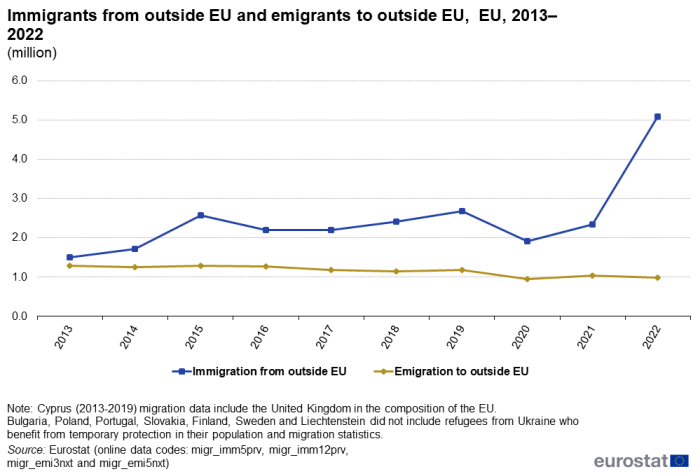

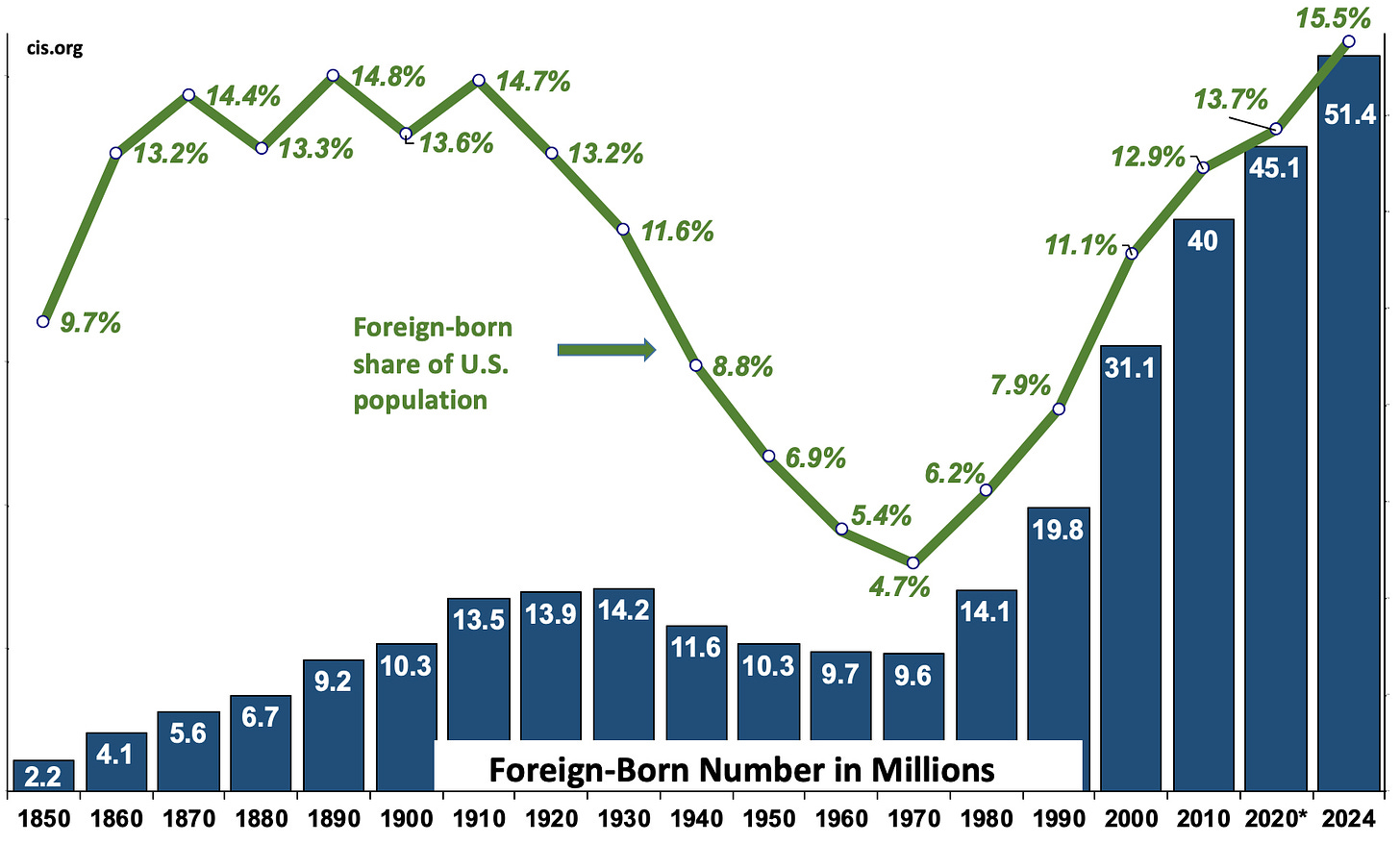

What interests me here is that while this was going on all three places – United Kingdom, Eurozone, USA – have experienced a large increase in mass third-world, which is to say non-EU, immigration since 2020. Politically all three places are also experiencing a ‘backlash’ to this ‘shock’ of immigration in the form of right-wing populist parties rising and taking vote share from leftists and centrists. In the Eurozone this is highly visible in figures such as Wilders, Le Pen, and Meloni, as well as the AfD in Germany. In Britain, it is represented by #ZeroSeats for the Tory Party and the recent re-appearance of Farage onto the scene, who if nothing else is set finally to win his own seat and enter Parliament. In the USA, it is of course represented by Trump and his continued struggle to remake the Republicans in his own image. Take a look at the following graphs, which show recent immigration in all three places, and flick your eyes back to the M1 Money supply charts.

It is remarkable how every region in the West follows basically the same trend: that this is a deliberate policy cannot really be doubted. What I want to do here is to work out the economic rationale for this. Covid money printing increased from about £1.75 trillion to around £2.3 trillion. That is the total amount of money in the British economy. The government do not want that money just sitting there, they want people spending it. Thus, roughly speaking, £2.3 trillion can be said to be the total ‘demand’ in the UK for people to buy television sets, apples, and whatever else. The increase from £1.75 trillion to £2.3 trillion is an increase of 31%. Given what I have said above, I would expect the price of goods to have increased by around the same all other things being equal.

Let’s come back to those apples now.

Here you will see that over Covid, between 2020 and 2022, there was around a 25 percent increase in the price of apples, as we would expect, but then they came back down just as the government increased the total number of people in Britain through immigration. Notably Jeremy Hunt was imposed as Chancellor during this same period. Since the money supply did not reduce relative to apples, the price was surely brought back down by some other factor. I propose this other factor is the exchange ratio between the M1 Money Supply and the total population, namely the additional 3 million imported since Covid. Again to keep this super simple, imagine a village has 100 people with an economy of 1000 gold pieces between them. The exchange ratio between money to people in this economy is 10 gold pieces for every person. What the government has done is added the equivalent of an extra three people to this village. So now the exchange ratio is 9.7 gold pieces per person rather than 10. Naturally, yes, this makes every person worse off, but if every person now only has 9.7 to spend as opposed to 10, you can see it would have a slightly deflationary effect on the prices of things they can spend their money on. This is very visible at the tiny scale of one village in a fictional economy, and our government is thinking on a very wide and mass scale which masks the nuts and bolts of what is happening.

It is suggested that the minimum monthly cost of living in the UK for a single person including rent is around £2,000. That means one immigrant theoretically represents £24,000 a year being spent in the UK economy, which, in turn, means that 3 million immigrants represent about £72 billion a year being spent. The extra Covid printing, as we have seen, was around £550 billion. Look again at the M1 Money Supply graph above and notice that Jeremy Hunt turned the taps off when he arrived in number 11, that is the money supply reduced from 2022 to 2023 while the population increased. Interestingly this is in line with what the Eurozone did as well with a similar drop in money supply at exactly the same time. Using these numbers we can see it would take the extra 3 million immigrants only around seven and a half years to ‘soak up’ the new money assuming the money supply is kept relatively stable. Via this mechanism, although each individual British person has been made worse off, as per my village example, the extra people partly offset the inflationary effects of the excess money printing during Covid. I offer this as an explanation for what the government has done, and although I have focused on Britain here, it seems at a glance that similar policies have been pursued in parallel across the Eurozone and in the USA.

I have been informed that articles on this exist here: https://thecritic.co.uk/the-follies-of-human-quantitative-easing/ and here: https://conservativehome.com/2024/02/16/tom-jones-immigration-and-the-recession-our-stagnant-economy-needs-to-be-weaned-off-its-addiction-to-human-quantitative-easing/. It appears that Tom Jones helped popularise this this phrase and it may have first been coined by Peter North as “quantitative easing with people” in this tweet: https://x.com/FUDdaily/status/1727306375288561759.

Very interesting point and reasoning. A couple of remarks as food for thought and critique of this theory. I speak from experience in Germany, and are not fully familiar with the situation in UK, but as you write, it is more or less the same in all white countries.

1. Generally, the analogy of "soaking up" of money supply by imported third worlders would mean that money supply remains stable, which it does not, especially not in the EU. 75% of the new arrivals (whom a Green Party "memberette" deemed more valuable than gold) are and will remain on government sponsoring. Also, their number is constantly growing, meaning new influx in these government programs. These can only be maintained by an increase in the money supply, i.e. government debt. Taxation alone does not cut it. Hence, as the supply increases, there is no net soaking up of previously created money supply. It just keeps adding and adding, the soak-up-effect is always one step behind, so to say. If government would want to quantitatively ease existing money supply, they would have at least to reduce the spend per new arrival over time, which it doesn't.

2. Taxation rates have not increased (yet), because this would make the money transfer to new arrivals all the more obvious. Granted, total tax amount received by state has increased, as a second order effect of the inflation the state created (isn't that nice). This back ups the fact that new arrivals require new money coming from debt. Taxation could be more deflationary, but due to it being highly unpopular, the regime has not touched it yet.

3. Total money in the hands of more people does not mean that this has a deflationary effect. Yes, individual spending power goes down. However, let's assume that apples provide a necessary good, without which one cannot live. More people now competing for the same amount of apples would actually mean that prices go up. One has to look closely at the good under consideration whether "money in number of people hands" has an inflationary or deflationary effect. Basic goods most likely will be inflated, given constant or reduced supply. Reality shows, think housing, food, energy.

To conclude, this comes down to a cause-and-effect question. Were new arrivals brought in to reduce the effects of inflation, you would have to see a drop of prices as a consequence.

Rather, I would say, new arrivals contribute to an increase in inflation due to the increased demand (housing being the best example).

What has contributed to the rate of inflation easing over the past two years (prices are still net-increasing) is the manipulation of energy markets, FX markets and bond markets by the BoE, ECB and its minions in the European banks.

The import of millions of third worlders is a goal in and of itself, that the regime (and another force I will not mention, but everybody knows) follows in order to destroy the fabric of white countries and make them more governable for globohomo (at least, that is the regimes theory).

You're on the right track here. Where this type of analysis will really shine is if you can connect it to trends in borrowing, especially amongst the new arrivals. It isn't enough to simply have them soak up increases in the money supply; the system desperately needs to lever them up with fresh debt to back the issuance of future money to keep the merry-go-round turning.

The West is showing all the signs of being caught in a debt trap since the 70s, when the monetary system was decoupled from the material economy of gold or energy. Since then, every economic policy has just been kicking the can down the road in one way or another. In the end, they will pull every trick to mask bankruptcy, from replacing attempts to merge sovereigns, inflate populations. The next trick will essentially be the re-imposition of rationing under the guise of CBDCs, or war.

Unfortunately, a monetary system running on interest demanding ever increasing returns is like a control system with infinite positive feedback. It cannot operate in a steady state, but must instead grow exponentially until it falls over. This is a result of the math of control theory that economists would do well to read up on.